‘Necessity drives invention, but sometimes it needs a nudge.‘

For centuries, incentive challenges have driven innovation to address critical needs. Take canned food, for example. In the late 18th century, as the French sought to expand their empire, they faced a challenge: how to feed an ever-growing army during prolonged wars? Fresh produce wasn’t available year-round, nor could be transported over great distances. The problem was clear, but the solution was not. Napoleon Bonaparte offered a prize of 12,000 Francs to anyone who could solve it. Nicolas Appert, a resourceful Frenchman, developed the first food preservation method by canning food in glass bottles, winning the prize. Another Frenchman, Peter Durand, improved the method with tin cans in 1810, creating a market now valued at $100 billion.

Incentive challenges unlock potential across various issues, from food preservation to human longevity. But their success hinges on a well-crafted problem statement—one that clearly defines the need, sparks ambition, and attracts key stakeholders. In the development sphere, especially where markets serve the underserved, understanding the nuances of supply and demand is essential. Identifying the right problem is crucial to the success of an incentive challenge.

The problem statement of an incentive challenge not only defines the need but also sparks ambition and attracts the right stakeholders. In the development sector, where markets aim to serve the underserved, these challenges are more complex, requiring a deep understanding of the incentives on both the supply and demand sides. This makes problem identification critical to the success of the challenge.

Problem identification at The/Nudge Prize is broadly a three-stage process

Before we go into the specifics of each of these stages, it is important to outline four key principles that guide our design process:

- Design is a collaborative process: A challenge’s ecosystem is key to identifying problems and understanding on-ground issues. It also helps get buy-in from various players in the development sector. At The/Nudge Prize, we work with a third-party agency to shape and validate hypotheses, alongside our research team. We also consult experts and practitioners to pinpoint bottlenecks and tech needs across the value chain.

- Livelihoods and technology are core: At The/Nudge Institute, we focus on creating solutions that enable sustainable livelihoods for India’s most vulnerable populations, such as small farmers and micro-enterprises. We’re particularly interested in tech-driven solutions that address socio-economic issues and improve the livelihoods of these groups.

- Incentives are key: Problems often stay unsolved when incentives are unclear. For instance, the DCM Shriram AgWater Challenge tackled sustainable water use for small farmers by addressing incentives for both farmers and problem solvers. Small farmers may not prioritise water use but are drawn to ideas that boost income, like better yields or lower costs. Market factors like MSPs (Minimum Support Price) also influence their choices. By focusing on these drivers, the challenge encouraged farmers to adopt water-saving practices, creating opportunities for innovators in the process.

- Perfection is the enemy of the good: Perfection can get in the way of progress. Incentive challenges need to strike a balance—ambition vs. feasibility, deep vs. broad impact, and more. While the perfect problem statement might be ideal, it’s more important to aim for a practical and achievable one.

If we still have your attention, then let’s get into the details of the process.

Stage 1: Distilling the landscape

Big problems are complex, with many moving parts buried under noise and clutter. The distillation stage helps cut through this to uncover clarity and gain key insights.

We begin with a literature review—scanning datasets, reports, blogs, and podcasts—to identify initial threads and build an inside-out view of the problem. This perspective is sharpened through consultations with experts, thought leaders, and practitioners, and further enriched by field visits to meet problem solvers on the ground.

Field visits to understand the women-led enterprises for the upcoming The/Nudge Prize

This isn’t a quick process—it can take 2 to 6 months, depending on the complexity of the issue and the availability of reliable information. It’s iterative, often requiring multiple rounds of refinement.

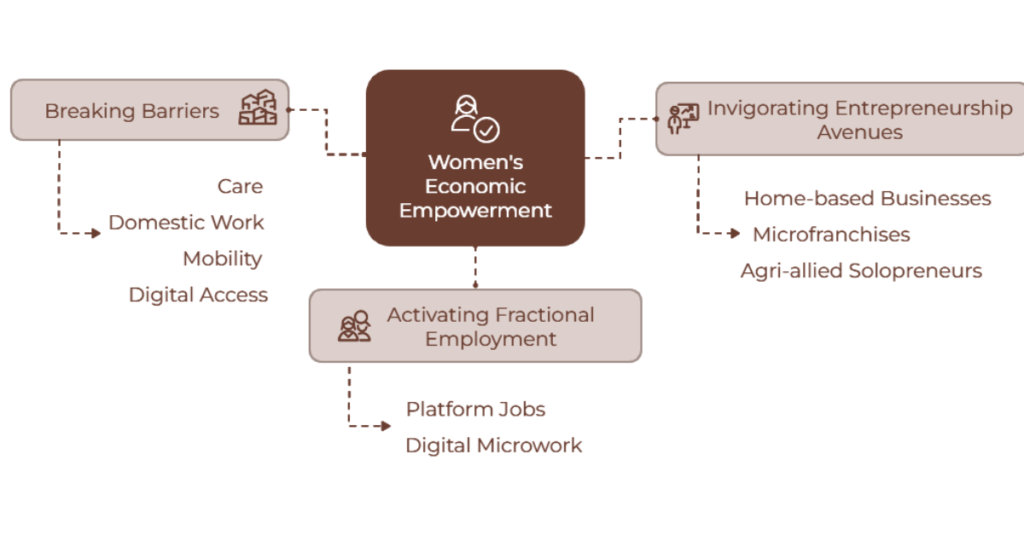

By the end of the distillation process, two key outcomes emerged: focus areas or population segments with high potential for impact and a broad understanding of what must be done. For instance, while exploring the female labour force landscape, we prioritised segments like home-based entrepreneurs and livestock farmers, among others. We also identified three solution areas: enabling fractional employment for women with time and mobility constraints, boosting entrepreneurship opportunities, and breaking barriers to sustainable livelihoods.

These findings helped refine our problem statement for our latest Prize—The Digital Naukri Challenge, a part of the Future of Women in Work series.

Stage 2: Building the vision and roadmap

If the distillation stage is about identifying the problem, the roadmap is where we chart the course to solve it.

A roadmap breaks a big problem into smaller, interconnected pieces, often sequencing them—some issues must be resolved before tackling others. It starts with the insights from the distillation stage, such as target segments or focus areas.

- We draft a 10–20-year vision for the chosen segment, outlining an ideal future. For instance, a vision for homemakers may include increased workforce participation or skill development. An example is the Digital Naukri Challenge, aiming to create 1 million digital jobs for homemakers by 2030.

- Next, we pinpoint the bottlenecks blocking this vision. This involves group consultations or listening circles with experts—practitioners, academicians, and investors—who help uncover real challenges. For example, our listening circles helped us understand that women entrepreneurs face inconsistent demand, limiting income and access to solutions like credit or training.

- Not all bottlenecks are market-solvable. Some require government or civil society intervention. For market-driven solutions, we focus on areas where incentives are broken. The listening circles help identify these dormant opportunities, such as how technology could streamline fragmented supply chains for local sourcing. For instance, fragmented supply chains may block local sourcing, and technology solutions like standardisation or spoilage reduction could unlock demand.

- Finally, we assess each problem area for feasibility, focusing on solutions with strong support from problem solvers and buyers. High-density of problem solvers and potential buyers are prioritised for their sustainability beyond the challenge.

- This process highlights 5–7 actionable focus areas that form the foundation of the roadmap, paving the way for systemic, scalable impact.

Stage 3: Designing the problem statement

A problem statement defines what needs to be solved and sets clear goals for participants. If it’s unclear, it creates confusion and undermines the challenge by making it hard to identify the best solutions.

The level of specificity also matters. A broad statement, like “Increase women entrepreneurs’ income by 40%,” can attract diverse solutions—marketplaces, credit models, training, etc.—but makes it hard to compare them fairly. Conversely, a statement that’s too narrow, such as “Design a credit solution with less than 5% interest, flexible repayment over 3 months, and Android 8 compatibility,” can limit creativity and discourage participation. A well-crafted problem statement inspires action and impact while striking the right balance between focus and flexibility.

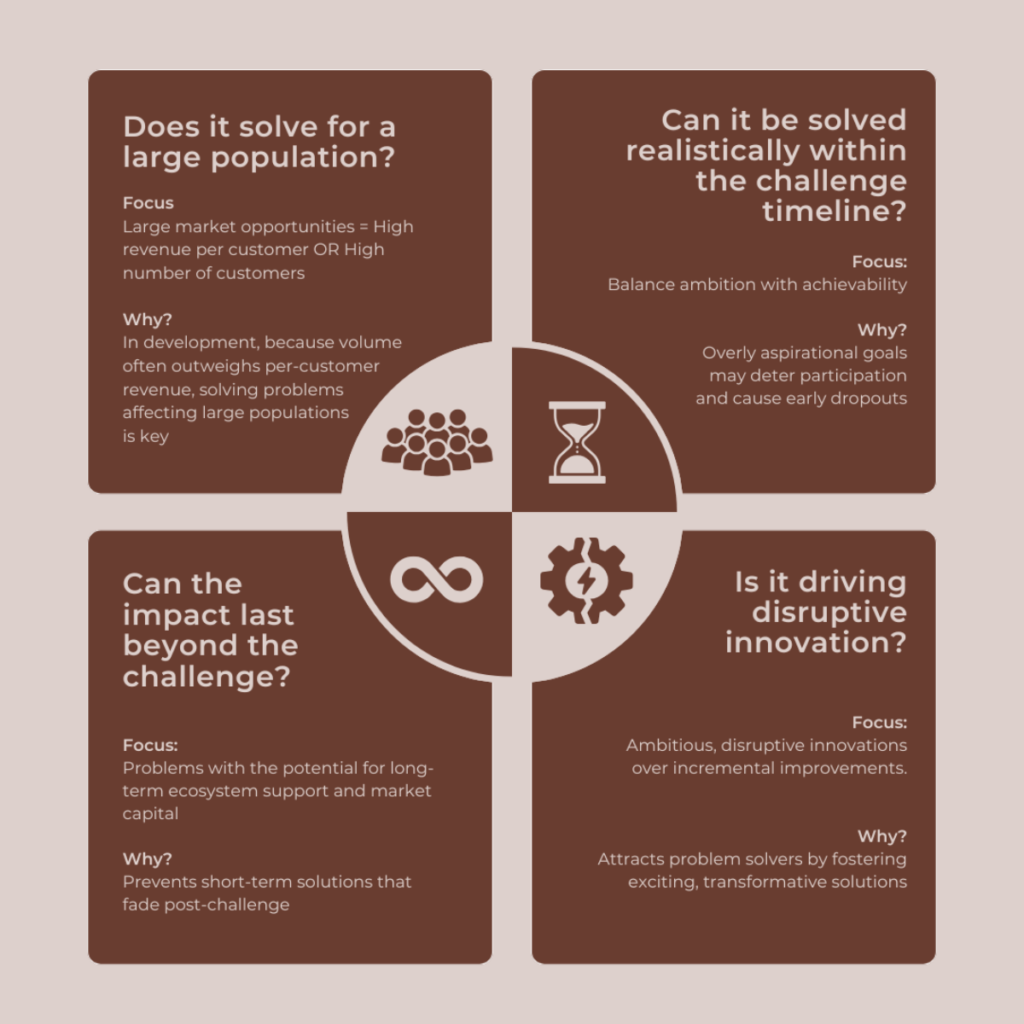

A well-defined problem statement serves as the foundation for action, enabling meaningful impact within a specific domain or geography. To drive action and ensure lasting change, it must meet four essential criteria.

Designing a strong problem statement is like building a roadmap, but it goes deeper, narrowing in on specific challenges. This requires insights from experts who live and breathe the problem.

Experts tend to focus on two key aspects: improving access or enhancing the efficacy of the tech solution. While access is about making technology more affordable, efficacy means boosting productivity or optimising resources.

Once we pick our challenge—access, effectiveness, or both—we dive into a current state analysis, examining existing solutions from every angle. With expert input, we then map out the future state. Clear thresholds are set, whether it’s lowering costs or increasing adoption, ensuring challengers know exactly what success looks like.

Despite all the checks in place, problem statements can still lead to unexpected results once the challenge kicks off. But rather than getting discouraged, learning from the experience and applying those lessons to improve the next iteration is key.

Through this blog post, we’ve shared why identifying the right problem statement is crucial for incentive challenges and outlined our approach to it. While our passion for the subject lets us go on about it, we hope this post serves as a clear and engaging summary, sparking more discussions on how to refine the process. In the next part of this series, we’ll explore how The/Nudge Prize drives change throughout a challenge’s lifecycle and dive deeper into our ecosystem design and planned interventions. Stay tuned!