“Five or six of us women from our group went to the BDO office multiple times to address the lack of drinking water in our tola. During one visit, we saw the Village Mukhiya and brought him with us to the BDO office to address our concerns. Eventually, we were able to communicate our situation, explaining the severity of drinking water availability to the BDO and invited them to visit our tola and see the situation first hand. Then the BDO visited our tola to assess the water issue,” recounted Gudiya Devi and Savita Devi Didi.

Seated in the sunlit courtyard of Gudiya Devi’s mud-plastered home, the two women share how their community in Parhaiya Tola—once struggling with basic needs—secured two borewells and saw sixteen families benefit from the PM Awas Yojna (housing scheme). Just a few months ago, their village had only one well, which was not drinkable and dried up every summer. When asked whether they considered running for local office, they laughed, dismissing the idea. “We are illiterate, it is impossible,” they said.

Parhaiya Tola

Parhaiya Tola, where Savita Devi and Gudiya Devi live, is home to the Parhaiya community, classified as a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG). Traditionally, the Parhaiyas depended on collecting forest products and making medicines and handicrafts from them. There are 25,585 Parhaiyas (per the 2011 census), with the majority in Jharkhand. Due to low literacy levels, a declining population, the use of pre-agricultural technology for farming and general economic exclusion, they were identified as PVTG.

However, with increasing deforestation and loss of access to forest resources, their traditional livelihoods have been severely impacted. Despite these challenges, the community’s deep-rooted knowledge of nature still plays a vital role in their daily lives. Savita Devi, for example, demonstrates the use of the Satyanashi plant (Mexican prickly poppy), a thorny plant with yellow flowers, explaining how she uses its boiled extract to treat toothaches—a practice passed down through generations.

From annual migration to stability

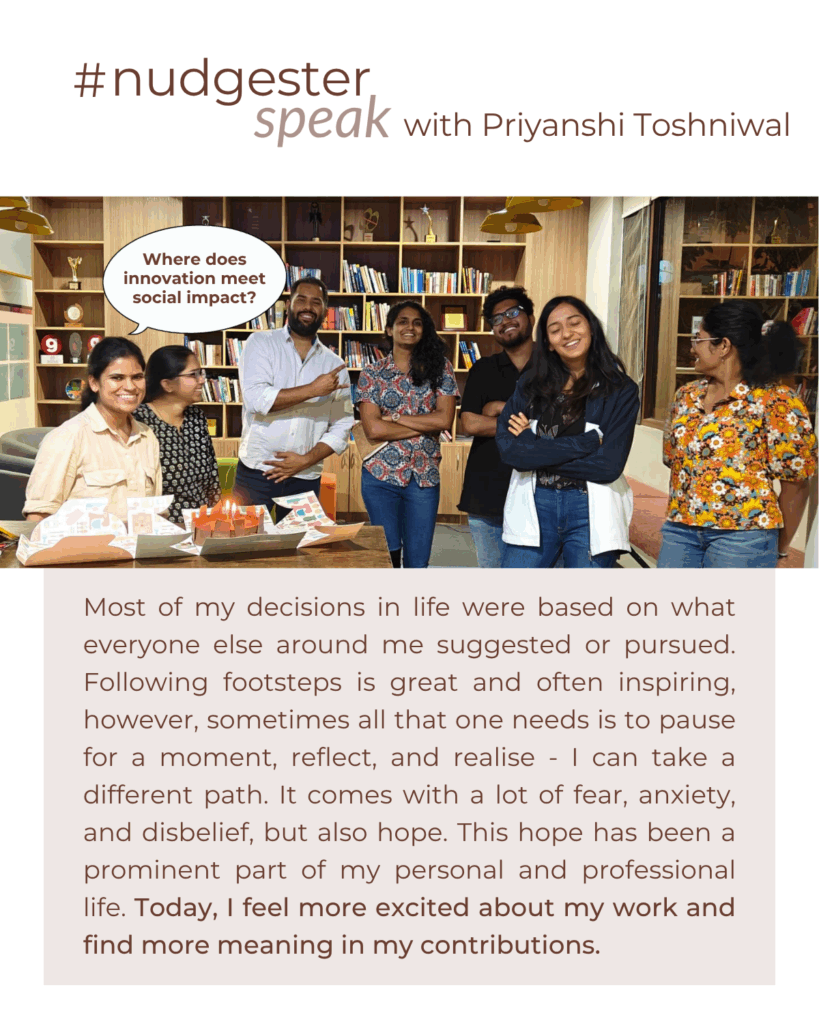

The/Nudge Institute began its Economic Inclusion Program (EIP) implementation in the Damodar Village in 2019. Prior to joining the program, most families, including Savita and Gudiya’s, migrated seasonally to work in brick kilns in cities like Benaras and Tripura. These migrations, although a source of income, came at a significant personal cost.

Kanti Devi, another participant in the EIP, recalls how she and her husband, along with their children, would migrate to Benaras for work and live there for six months every year. But as the children grew older, she had to leave them behind in the village.

Gudiya Didi says that if they took their children to the brick kilns in Tripura, they would miss school. In these brick kilns, their families worked long hours—often 10 hours a day—making up to 400 bricks a day for a meagre ₹240, amounting to ₹7200 for 30 days. Often part of their earnings goes to Sardars or middlemen who acted as both employers and moneylenders.

Handholding to sustainable livelihood

“Before joining the program, we planted only maize; we would also keep goats but they wouldn’t survive. They would die due to loose motions, or illness or something.” says Gudiya Didi, while Savita Didi proudly chimes in how villagers now ask them, “What are you doing that your goats are healthy but ours die during the monsoon.”

After graduating from the Economic Inclusion Program, both Gudiya and Savita Didis became Pashu Sakhis (TRPs), trained to give vaccinations, medicines, and advice on goat rearing to villagers. Beyond supplementing their income, this has cemented their self-confidence.

Gudiya Devi’s family now owns 14 healthy goats, and Savita Devi has 10. Over the past three years, Gudiya Didi has earned ₹90,775 from goat rearing and other program-supported activities. Savita Didi, in turn, earned ₹68,000. The impact of these efforts is evident in their growing confidence and the respect they’ve earned within their community.

Kanti Devi, who also participated in the program, now has 13 goats and earned ₹16,200 from selling three goats. She also earns over ₹15,000 annually from crop sales. Kanti Didi emphasises that even though the program has ended and the Dadas (CDOs) don’t come regularly anymore, her family will continue to flourish, “It also depends on us; I will work harder and grow further.”

“We learnt continuously through the training process. Dadas (CDOs) would tell us that at this time do this and gave us books to look at, which show us and help us understand when and how to carry out activities in cultivation and goat rearing.” – says Gudiya Didi

Building confidence and leadership

One of the most significant outcomes of the Economic Inclusion Program is their self-confidence. They say, ‘meeting regularly with changemakers and interacting with various stakeholders has made them confident about their abilities and they hope to meet us again.’

As they bid us goodbye, Gudiya Didi and Savita Didi reflected on their journey and how they never imagined they could speak up in front of officials. Now they break off wondering, “Why can’t we become a mukhiya, maybe we can, we can try, we will also see if we can.”