This article proposes a conceptual framework for assessing the impact of graduation-based poverty alleviation programs beyond income. Grounded in real-world insights from The/Nudge’s Economic Inclusion Program (EIP), it maps the nuanced, non-financial shifts in women’s journeys out of poverty.

Why do we need a new lens?

Did you know that over ₹1 lakh crore was committed by nine Indian states last year toward direct cash transfers for women? From Karnataka’s ‘Gruha Lakshmi’ to Maharashtra’s ‘Ladki Bahin’, these initiatives signal an evolving focus in welfare policies, placing women at the centre of development efforts.

Beyond policy lies a deeper inquiry: what really happens when cash is placed directly in the hands of women, especially those in rural areas, those facing extreme exclusion, and those trapped in intergenerational poverty?

Our work under The/Nudge’s Economic Inclusion Program (EIP) in Jharkhand offers a glimpse into the answer. The program, which combines direct cash transfers with livelihood promotion targeted at women, has seen transformations that go far beyond bringing financial stability. We observed a significant shift in women’s agency to choose for themselves. We noticed a transformation in how women aspire before and after the program, reflecting newfound confidence and a desire for stability and growth.

Take Lalo Devi’s story, for instance–

How do you often picture a woman in a remote village in Jharkhand? Quiet, dependent, living in a fragile dwelling, her life revolving around her husband and children, with little room to imagine a different future. For years, Lalo Devi from Kotna village, Jharkhand, lived that very reality. While her husband migrated to brick kilns in Banaras, she stayed behind, raising three children amidst food insecurity and limited opportunities.In 2019, Lalo Devi’s household was identified and picked as one of the most vulnerable households under The/Nudge’s Economic Inclusion Program. In June 2024, when we met Lalo Devi after four years during a field survey, the change was evident—not just in her income, but in how she carried herself. Lalo had turned her 10-decimal plot into a vibrant livelihood, rearing 23 goats, cultivating and selling vegetables, and independently funding her children’s education. Lalo spoke about her participation in village committees, her savings to install a borewell so that her vegetable farming is not affected by drought months, and her aspiration of building a ‘pucca’ house. She expressed with pride how women in her village now ask her, with admiration, ‘how she managed to achieve it all on her own!’

Stories like Lalo Devi’s reveal that while income gains are important in poverty alleviation programs, they don’t tell the whole story. These include simple shifts like confidence in handling calculations, reduced hesitation in interacting with strangers, courage to step outside the home, or negotiating with customers. They also show up in the form of agency to make investment decisions, build networks, and nurture hopes and aspirations.

These subtle, deeply personal changes are harder to measure, yet they are key to shaping and sustaining a woman’s long-term journey out of poverty.

To address this gap, we developed a conceptual framework that goes into capturing nuanced changes and subtle behavioural shifts among women as they progress out of poverty.

How did we arrive at the framework?

The conceptual framework stands on the shoulders of giants and stories that we heard, observed, and interpreted from the field of our Economic Inclusion Program. It draws from well-known frameworks like the Harvard Analytical Framework, Longwe, Moser’s Social Relations, and Amartya Sen’s capabilities approach. These provide a strong theoretical foundation for understanding women’s agency and empowerment.

But theory alone isn’t enough. Our framework also takes shape from the everyday realities of marginalised women in rural, tribal, and excluded parts of India. Women who are figuring out how to track their income, deciding when to sell a goat, or walking into a bank for the very first time.

Co-created with Catalyst Management Services and rooted in both research and field insights, it offers a fresh lens to assess deeper shifts, focusing on agency, aspiration, and access often overlooked by traditional evaluations.

Framework for evaluating poverty programs beyond Income

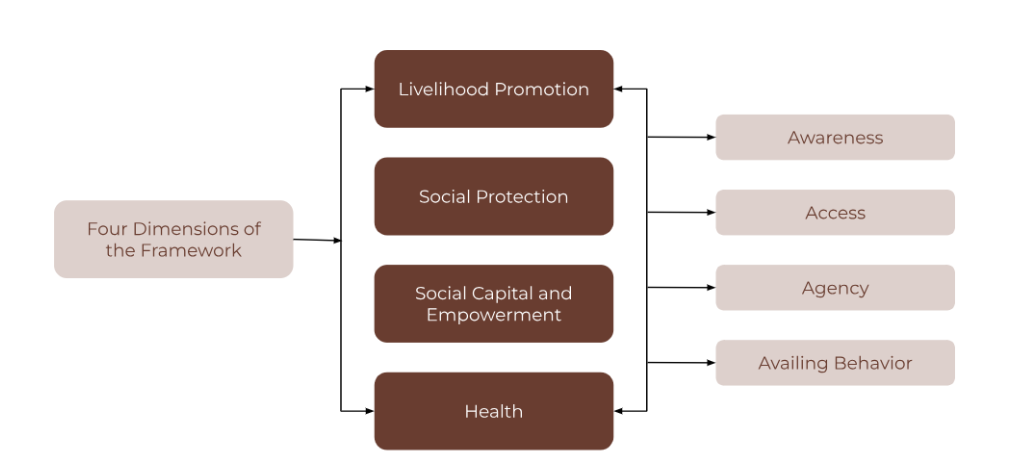

The core of our framework centres around social protection and livelihood promotion for women, which are foundational to the EIP and closely tied to the Graduation Approach. While we maintain these boundaries, we have also broadened our perspective by incorporating a few additional dimensions, such as health and social capital. The framework, therefore, focuses on four key dimensions centred around women:

- Livelihood Promotion: Is she generating sustainable income through a diversified livelihood?

- Social Protection: Is she able to access and benefit from welfare schemes and financial services?

- Health: Is there an impact on nutrition and overall health-seeking behaviour?

- Social Capital and Empowerment: Is she building strong networks, gaining confidence, and influencing decisions in her family and community?

Each of these dimensions is assessed through four levels for impact:

- Awareness: Does she know avenues to achieve outcomes in the desired manner?

- Access: Does she have the facilities and services needed to achieve the outcomes?

- Agency: Does she have the capability to influence decisions needed for the outcome?

- Availing Behaviour: Is she actively taking action to exercise her due benefits?

Conceptual Framework for Evaluation from a Gendered Lens

Telling the whole story

Evaluating poverty alleviation isn’t straightforward. Income gains are often the most visible and measurable signs of progress, and they undoubtedly matter. However, as we’ve seen through stories like Lalo Devi, they’re only a part of the picture.

This framework is a step toward making the quieter, deeply personal shifts of participants in poverty alleviation programs not only visible but also valued. Capturing such change isn’t about adding more questions to long surveys. It’s about shifting our lens: listening more deeply, designing more thoughtfully, and valuing stories as much as statistics. These are the changes that often sustain impact long after programs end.

We’ll continue building on this work with more pieces, exploring how to measure what truly matters and telling the whole story of impact evaluation.